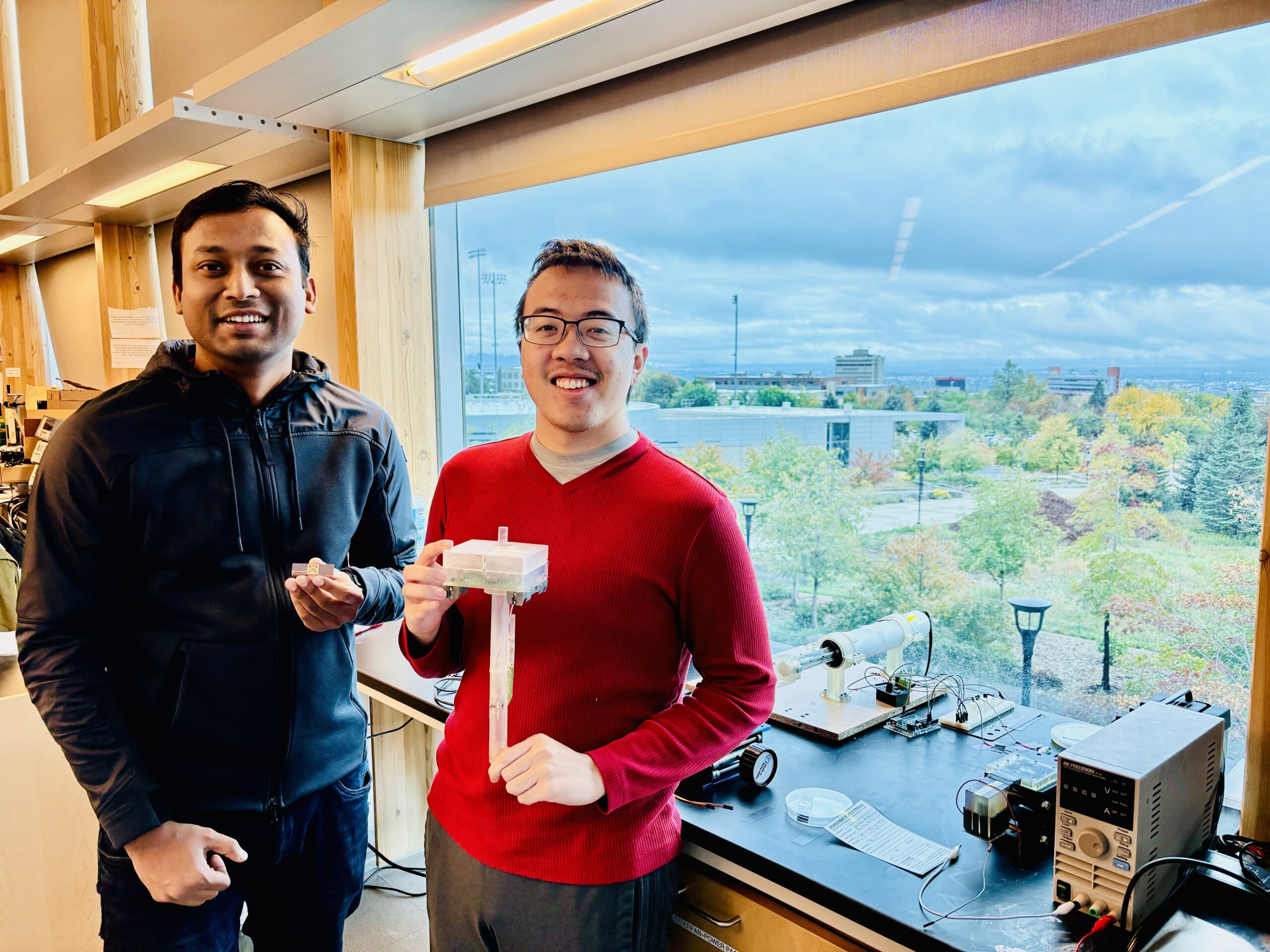

Last year The Wilkes Center for Climate Science and Policy hosted the first Student Innovation Prize competition where students could submit their most creative solutions to climate change. Steven Tran and Rabiul Hasan are Ph.D. students in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering here at the U, and they took home the third place prize last May. Their innovative proposal is an organic carbon measuring network that could be used to more accurately measure carbon content in soils. Their technology would make it possible to utilize agricultural land or even just our backyards to combat climate change or to improve our agricultural yield and processing.

Listen to the Interview

Transcript

Margaret 0:00

Welcome, guys! So, if you wouldn’t mind, would you tell me a little bit about your project and what you’re researching?

Steven 1:07

So, my research is primarily on this device where we’re trying to measure soil organic carbon accurately within the soil. At the moment, soil organic carbon is measured primarily through lab-based methods which are expensive, take a long time and are very accurate. However, with our technology that we’re researching, we hope that we can build a device that anybody can use; something that’s cheap, something that’s quick, and something that’s also accurate, as accurate as all the lab-based methods.

Rabiul 1:40

So, we are part of the same project, but we are dealing with two different sides. So, he’s mainly doing the integration part and I am working with making the sensor itself. What people are currently doing, they’re taking the sample to the lab and analyzing the sample and we are trying to offer a cheaper option. I am personally working with a sensor that is cheap and we can do batch fabrication so we can make so many sensors together. And also, we can scale it for some other gases as well. Like right now our focus is carbon component or carbon gas, but we can make it work for some other gas, like nitrogen gas that’svery important for agriculture as well. So yeah, that’s the things that I’m working on right now.

Margaret 3:04

Cool! Are there similar technologies being developed like yours or you guys the first ones?

Steven 3:11

Yeah, At the moment there are a couple in terms of in-situ based technology. Some of them are like drill based FTiR sensor where they’re drilling a sensor into the ground and measuring it based on FTiR. We are using a similar method where we’re also putting a probe into the ground and measuring it through an iR based method. However, we’re trying to simulate something that lab-based methods do, which is trying to actively extract the carbon from the soil itself. We do this by utilizing a U.V. LED, which is that cheap compact system that we can put into the ground. And by using UV, we found that UV can actively photo-oxidate and dissolve the organic component of the soil. This produces CO2 which we can sample, capture and correlate to how much organic carbon is within the soil.

Margaret 4:01

Awesome! So, what inspired you to start working on this particular idea? How did you get into it?

Rabiul 4:11

Okay, so I am originally from Bangladesh. It’s an agrarian country, so the economy is mostly based on agriculture. And it is a small country, like 57,000 square miles and smaller than Utah, like I think it Utah is around the 80,000 miles, and [Bangladesh] is accommodating almost 170 million people. So like agriculture is very important for Bangladesh, and we need to feed this big number of people. So, when I found about this project I feel like, ‘oh, this is a cool project to contribute for this big problem for the world’. Like how you are dealing… like the next extension of this project that I was talking about, for the nitrogen detections or something like that, you can understand how much fertilizer you will need. So, you are not going to waste and this is real time, so you will understand how much you really need every time based on humidity, temperature or many other environmental factors. So, I found it like okay yeah. This is really directly impacting people’s lives. So yeah, I found it very inspiring to work on this project.

Steven 5:57

To add on to that, I found that this project was very interesting, in that global climate change is a growing concern everywhere and people are trying to solve it. However, there’s just so much land that’s unoptimized that there’s so much things that we could do to resolve this problem and by utilizing this type of technology. When I saw this initial proposal, I found like even a person or normal person can use their backyard to optimize their soil such that they can actively restore or help mitigate global climate change. Through some calculations, theoretically, if the whole United States or everyone utilizes their backyard to optimize, they could technically store up to one gigaton, almost one gigaton carbon, just in the United States alone.

Margaret 6:45

Wow, that’s crazy. So your technology could be used not only to help with climate change, but also to optimize like agricultural yield as well? Okay, that’s cool. I didn’t realize that. Could you explain in like a little bit of layman’s terms (because I’m not a chemical engineer) how an individual could use your technology in their own backyard? Like how would they be able to do that?

Steven 7:09

So, yeah, at the moment it’s just a probe that you place in your soil. It has a resolution, spatial resolution, of approximately ten meters by ten meters. Once you place it into the ground, when you turn on the UV, you can see a jump in CO2 that’s captured by the device. We haven’t got a released app yet, but we have a graphical user interface where you can constantly see how much carbon is being captured by this device. And this device will constantly update you in real time how much soil organic carbon is in the soil. And with that real time measurement, you can improve your soil by just adding nitrogen, using different plants, and you can see the difference in how that’s

Margaret 6:45

Wow, that’s crazy. So your technology could be used not only to help with climate change, but also to optimize like agricultural yield as well? Okay, that’s cool. I didn’t realize that. Could you explain in like a little bit of layman’s terms (because I’m not a chemical engineer) how an individual could use your technology in their own backyard? Like how would they be able to do that?

Steven 7:09

So, yeah, at the moment it’s just a probe that you place in your soil. It has a resolution, spatial resolution, of approximately ten meters by ten meters. Once you place it into the ground, when you turn on the UV, you can see a jump in CO2 that’s captured by the device. We haven’t got a released app yet, but we have a graphical user interface where you can constantly see how much carbon is being captured by this device. And this device will constantly update you in real time how much soil organic carbon is in the soil. And with that real time measurement, you can improve your soil by just adding nitrogen, using different plants, and you can see the difference in how that’s affecting the organic carbon within your soil.

Margaret 7:57

Moving forward, what kind of like real world applications, what where do you how do you see this becoming more widespreadly implemented? How do you see that, like trickling forward?

Rabiul 8:11

That’s you.

Steven 8:12

Yeah, so…

Rabiul 8:14

He’s working with the integration portion, so yeah.

Steven 8:18

So hopefully, the hope is for this technology to be utilized worldwide by everybody. By anybody who has a backyard, you can place this in the ground. And Rabiul mentioned that at the moment we’re only measuring carbon, but in the future, we’re going to be implementing different ways to measure other gases such as nitrogen, methane, so on and so forth. That way, people or any regular person can optimize the soil in such a way that global climate change is mitigated as much as possible.

Margaret 8:48

Cool. That’s awesome. What kind of like response have you guys gotten to your findings in your research and what have people said about it?

Steven 9:02

Actually, we’ve gotten pretty good reviews from other people. Last year or last October, we went into a soil organic carbon competition sponsored by Bayer and we actually got second place in the world in terms of measuring soil organic carbon, in terms of accuracy and how rapid the measurements is and even at that point it was still an incomplete prototype (click here for more information on the competition). But, as of right now we believe that we’ve improved it tremendously, in an exponential amount of way that we may have the best technology in terms of measuring soil, organic carbon in-situ with the soil also like.

Rabiul 9:41

So, we are like publishing those works or sending them to the conference. So I want to add, my conference report that I submitted I see that like I got very good review from their reviewer in this field and also that work is nominated for best work or paper there. So, I’m going to Austria for presenting my work there. So it seems like everyone likes the idea.

Margaret 10:11

So that’s awesome. Yeah, it’s great that it’s so well received. So I guess like just a little bit more of like a personal question about it. What’s been your favorite part of working on the project? What’s your favorite aspect of your research?

Steven 10:28

Personally, my favorite aspect is just seeing everything come together When you’re integrating all the different components electronics, circuitry, software. When you get to see all that work utilized by anybody in the field, you can see how special the device is and how it can really shape the world and how it can minimize global climate change.

Rabiul 10:50

For me… So for this project, I started working with nanofabrication, and so my device size is like just width of two hair. And it’s really amazing for me, like how this small device is doing this tremendous job. Like, yeah, that really amazed me.

Steven 11:09

He has devices that are micrometer in scale you can’t see it by eye.

Rabiul 11:13

Yeah, you have to use optical microscope to see.

Steven 11:17

And you can measure all the carbon and stuff. It’s amazing.

Margaret 11:20

That’s crazy that it’s so little. So you guys talked a little bit about like your background, Rabiul especially. What is your background? Where were you before you were here and kind of what brought you to the U as a student? Why are you here?

Rabiul 11:40

Okay. Yeah. So I did my bachelor in Electrical Engineering in Bangladesh, and after my bachelors, I worked for a couple of years and I see that, like, I, I really want to do something that not things I have to repeatedly doing in the industry. So that makes me look for opportunity like I’m doing, research kind of jobs, and I see that like, yeah, I have to do PhD for getting qualified for those research positions. And definitely the United States is one of the best places in terms of like research funding and all these other opportunities. So yeah, that made me choose this country, you know, and yeah.

Steven 12:35

Yeah, similar to Rabiul, I also got a bachelor in electrical engineering from Boise University in Boise, Idaho. That’s where I’m from. After graduating, I wasn’t really sure what I was going to do with my life at the moment. I did some internship as an engineer back in Boise, in Micron, but like Rabiul, it was mundane, repetitive and it wasn’t something I really enjoyed. So, in the end I decided to pursue a Ph.D. in engineering and I found it much more enjoyable, much more fulfilling and challenging.

Margaret 13:10

Awesome. So after you’re done with your PhD or whatever else you decide to do with it, where do you want it to take you? Like, where do you want to move after this? Do you want to keep doing this soil carbon monitoring stuff? Are you going to try and do something different? What’s next?

Steven 13:30

For me, personally, I’m not particularly 100% sure what I’m going to do yet, but hopefully it’s going to be some type of sensor-based system integration or software development in which I can help with global climate change or any other problems that can help resolve an issue that is being a concern in the world at the moment

Rabiul 13:53

Okay, I’m not sure if I will stick with exactly these topics, but I see like different organizations like NASA, Department of Energy, different national labs. They’re also working with the approach we’re targeting, an optical sensor, and they’re also doing many research related to optical sensors to detect different kind of gas accurately and if it’s possible in cheaper way. So, I see that there are many opportunities around, so I’m not exactly sure where I will go, but yeah, I’ll keep myself in this. This field, I’m sure. Yeah.

Margaret 15:10

That would be awesome. Okay, perfect. Thank you so much for being here with us today and we appreciate all of your work and contributions. We’re really excited to see where it goes.

Rabiul 15:20

Thank you.

Steven

Thank you so much.