Listeners to the podcast are very likely familiar with the concept of carbon offsetting or carbon credits. This is the idea that a company that pollutes in the course of its business practice can purchase carbon credits, often in the form of supporting tree planting somewhere in the world, with a promise that doing this will remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, to “offset” or balance-out the company’s carbon pollution. This has become a billion-dollar global market.

But in recent years this practice has experienced a crisis of credibility. An increasing number of investigations and studies have eroded confidence in carbon markets. The carbon offsets for some projects were over-counted, while others didn’t actually prevent deforestation, and still other carbon credit forest projects appear to be much more vulnerable to wildfires or insect outbreaks than previously believed.

So, what is to be done? Can the carbon offsetting approach be fixed? Or, is a totally different approach needed?

Libby Blanchard, a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Wilkes Center, and the School of Biological Sciences here at the U of U, says that billions of crucial funding would best be spent on a contribution approach for effective forest efforts that don’t undermine urgent climate action. She recently co-authored an op-ed with other scholars in the Stanford Social Innovation Review journal to make the case for this new approach.

Listen to the Interview:

Transcript:

Ross Chambless

Well, Libby Blanchard, thank you so much for spending some time to talk with me today.

Libby Blanchard

Thank you for having me.

Ross Chambless

Before we get into the topic of your work with carbon offsets, can you briefly share a little bit about your journey before you came here to work at the U?

Libby Blanchard

Absolutely. I did an undergraduate degree in English literature, but I was always very interested in environmental conservation. And out of my undergraduate degree I went and worked for a specialty coffee importing company. And I started to write grants for them to do international development to help coffee farmers. And that led to starting to direct some of those projects and starting to work in 14 countries throughout the world to help coffee farmers. And that was very much what we call in academics an integrated conservation and development model, where we were helping coffee farmers produce higher quality coffee to get that coffee to the market at a higher price. But one of the ways you can do that with coffee as one of the few cash crops that you can do this with is plant trees and help the biodiversity around the coffee trees.

So, I did that for six years and then I was more interested in kind of the questions that came along with development. And I had some friends who encouraged me to apply to grad school and then I entered a master’s program.

Ross Chambless

Interesting. So, your work with coffee was sort of, would you say your introduction into the carbon offset, carbon credit area?

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, it was. So, this was 2006 to 2012. And this was right when the idea of planting trees to conserve carbon was becoming more and more prevalent. So, one of our projects was in Tanzania, in the national park where Jane Goodall did her research on chimpanzees. And while we were doing our own work and planting trees and helping the coffee farmers there, I was just noticing a lot of NGOs starting to get involved with this idea of tree planting or tree conservation for carbon storage.

Ross Chambless

And so, since you have become an academic researcher and you’ve spent quite a bit of time and energy focused on examining our current carbon credit market, the global market for this. Can you bring listeners up to speed on what are carbon offsets? What are they supposed to do? And what have been some recent developments in the carbon offsets market that have sort of called into question its effectiveness?

Libby Blanchard

Sure. So the idea of offsetting emissions, basically being able to emit in one place and then reduce or remove emissions elsewhere and then call that climate neutral, has been an idea starting around 1989 when the first tree planting project was started. I believe it was Guatemala, and it was with an energy company here in the United States, and they were trying to see if they could plant trees in Guatemala and then use the absorption of carbon from those trees to offset their emissions of a new coal fired power plant.

And then following that in 1996 and 1997 was the Kyoto Protocol negotiations. And in those negotiations, the U.S. and a group of another of other industrialized countries was really looking at this idea of carbon crediting and carbon offsetting and having market mechanisms and these flexibility mechanisms, which are basically carbon credits, carbon trading to make it more economically feasible for industrialized countries to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

So that’s kind of the first history of carbon credits and carbon offsets. A carbon credit becomes an offset when it’s used to trade against emissions somewhere else. And a carbon credit is supposed to be one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent reduced or removed from the atmosphere over a predetermined period of time. The big problem with carbon credits is a large majority are not real or are what we call over-credited, or both. Meaning that they’re not representing or are overrepresenting the amount of carbon dioxide equivalent actually reduced or removed for the atmosphere.

Ross Chambless

Interesting. So essentially, we’ve gotten to a point where there’s a lot of businesses that contribute, or like to say that they are contributing, a certain amount of carbon offsets, you know, money to support projects that are usually, I guess, tree planting as a way to kind of claim that they’ve offset their greenhouse gas emissions somewhere in their business stream.

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, that’s how the model has worked. Where companies are supposed to try to reduce their own emissions first and then look at their remaining or residual emissions and buy carbon credits to offset those remaining emissions. The problem is, again, offsets, a large majority of research has shown, don’t actually represent the one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent reduced or move that they’re supposed to do. And then there’s a durability problem which has come out of a lot of great research here at the University of Utah, where basically if you plant a tree, that tree unfortunately is not going to hold on to the carbon it absorbs forever. And so that tree represents temporary carbon storage versus the carbon that somebody emits when they’re driving to work today will persist in the atmosphere for centuries to millennia. So, there is… we call it the Incommensurability issue, where these tree carbon credits aren’t equivalent to the carbon that comes from fossil fuels that’s going to persist in the atmosphere for millennia.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, I see what you’re saying. So essentially there’s no guarantee that a tree planted today is going to grow up to be a large, you know, giant redwood that’s going to hold a bunch of carbon for hundreds of years. There’s there could be an insect outbreak. There could be a wildfire there. The tree could get cut down or catch some kind of disease and die. And then all that carbon is not stored. Whereas, you know, driving a heavily polluting vehicle is most certainly guaranteed to put carbon up into the atmosphere unless it’s reduced or prevented in some way.

Libby Blanchard

Yeah. And to reduce or prevent that, it needs to be a like for like balancing of carbon removal. And then we start to talk about “direct air capture” and things like that to remove carbon out of the atmosphere and store it underground for hopefully centuries to millennia, which is a really complicated stuff. And none of those carbon credits have scaled yet. And even if the tree that is sequestering carbon does stay alive for hundreds of years, it will one day die before the century or before the millennia is up. So, it represents a temporary solution to storing carbon, but not a permanent solution. So, I think a lot of researchers like me really look towards the importance of reducing direct emissions and not… and I guess we should say we worry about these offsets being a way that they could potentially disincentivize real emissions reductions or slow down real emissions reductions.

Ross Chambless

Right. And there has been, at least recently, kind of a reckoning with carbon offset market. And just to briefly quote your op-ed, you know, you said “there is a drumbeat of scientific articles, reports and investigations in the last year showing that the climate benefits of forest carbon credits have been greatly overestimated and that at least some offset projects have actually caused social and environmental harm.” So, it seems like we’re perhaps at a point where we’re looking at new ideas or looking for alternatives to the current system.

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, I think there are two camps right now with carbon credits, and there’s a big push amongst many people that the carbon credit market can be fixed. And I have become skeptical of that because we’ve had carbon credit markets since the Kyoto Protocol. So, since 1997, and we’ve had the voluntary carbon market arguably since around 1990 before that. And unfortunately, in most cases, the credits coming out of both of these markets have found to, in the majority of cases, be not real or to vastly over-represent emissions reductions or removals.

So, I am one of the people who’s skeptical that the carbon market can be fixed in its current form. But I think that there’s certain things that we can do to allow companies to still buy carbon credits but make more accurate claims about those carbon credits, and allow companies to invest in projects that might not go through the voluntary carbon market or be quantified in a in a carbon credit framework.

Ross Chambless

I see. So, this kind of turns to the idea of more of a contribution to projects. So can you talk about that and this this new approach that you’ve been exploring?

Libby Blanchard

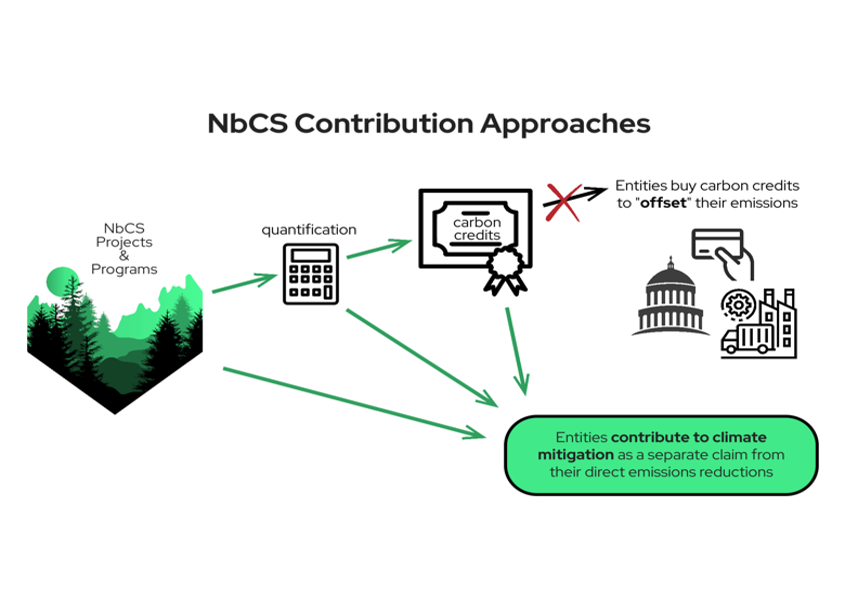

Yeah, it’s a great idea. It’s the idea that first and foremost we are more accurate about how we describe a carbon credit. Because like we talked about before, most of the carbon credits that currently exist do not represent emissions reductions or removals that will last over centuries to millennia. So, it’s much more accurate to say that when you buy a carbon credit, you are contributing to global climate mitigation, perhaps over a temporary period, but you could be contributing to temporary carbon storage. But you’re not truly offsetting your own emissions. Because, again, the carbon coming out of your smokestack or your vehicles will persist in the atmosphere and the active carbon cycle for a very long time where at least in the case of these land use, these tree planting or tree conservation projects, that carbon very well may not stay in that state, staying in biological storage for and for that period of time.

Ross Chambless

Yeah. And so why do you think… why is changing the terminology from offset to contribution is important. Why might that be necessary?

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, it’s really important to protect companies and keep people interested in having a climate mitigation strategy. I think a lot of corporations and probably the vast majority of corporations who buy these carbon credits are just trying to do the right thing, and they don’t quite understand how problematic the carbon credit market is. And it’s easy for them to buy carbon credits because the vast majority of them are very, very inexpensive. As low as $1 a ton for carbon dioxide reduced or removed.

And I would also say that a more accurate claim then protects them from legal and reputational risk. One of the big moments of change within the voluntary carbon market industry was when Delta got sued in federal court for calling itself the first climate-neutral airline. Because of some of these problems with carbon credits and because saying you’re carbon neutral can mislead a consumer into thinking that your product is better or more environmentally friendly, as in the Delta case, then like riding a train to California instead of taking an airline, when in actuality it’s not. So, there’s been this consumer protection movement and this rise of legal claims against companies who say that they’re offsetting their emissions.

Ross Chambless

Right. So, is part of this also an effort to make companies be more honest or to prevent groups to game the system? To, first and foremost, do that hard work of actually reducing emissions before turning to efforts to contribute or offset whatever remaining carbon impact they might have later? So, the current situation has been there’s just a lot of gaming of the system.

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, and in a lot of cases companies traditionally haven’t disclosed how much of their emissions they’re directly reducing versus how much of their emissions they are using carbon credits for to offset their emissions and claim that they’re carbon neutral or net zero. So, one of the things that we are pushing for and a lot of other people are pushing for, is for companies simply to disclose what their direct emissions are, how their direct emissions are changing over time. Are they increasing or decreasing? Because if they do have a climate commitment, they should be trying to decrease their emissions before looking into these various projects that they could invest in to reduce what we call “beyond value chain emissions” further.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, so I’m just wondering how you would imagine this sort of transition playing out if we indeed move into this new paradigm? If this new approach is embraced by different companies and sort of the existing markets that currently practice carbon offsets, would it require like kind of a global agreement, or would it just be more incremental? Like, different companies deciding, you know what, we’re not going to do this, we’re not going to make the claims of having a carbon offset credit anymore. We’re going to say that we are contributing this much to these projects instead. And kind of start at the business level incrementally. Is that perhaps how it could work?

Libby Blanchard

Yeah. So, the voluntary carbon market is completely unregulated, though there has been a push in the last few years to create these integrity councils to try to create principles for the carbon market. But yeah, I think this idea of just claiming that we’re contributing to climate mitigation as opposed to offsetting our emissions is most likely to take hold as companies continue to face these legal and reputational risks. There’s a lot of work being done in Europe and elsewhere to potentially even ban the offsetting claims or ban them if they lack a significant amount of justification. So, in some ways, I think there’s going to be a lot of movement towards this approach because it’ll be a safer approach for companies and a more accurate approach to talk about what they’re doing.

And then, within the compliance carbon market, which is the carbon market that’s trying to be developed right now by the UN framework Convention on Climate Change. There’s a whole other issue, and it’s maybe too technical for this podcast, but there’s this issue of double counting where if you have a project in, say, Tanzania, where we started our conversation and a company is buying credits from that project. But Tanzania as a country is also counting their countrywide emissions reductions as part of their nationally-determined contribution to meet their Paris Agreement goals, then that emission reduction is very likely being double counted, we say. And so, there’s been ways to address that double accounting issue, both within the UN official policy and within the voluntary carbon market. And one way to do that fairly easily is for the private company investing in these developing countries to just say that they’ve contributed to climate mitigation and not try to claim that credit or that emissions reduction, that quantified emissions reduction that the country also is claiming.

Ross Chambless

Right? That makes it make sense. As I mentioned before, you recently co-authored an op ed in the Stanford Social Innovation Review with Barbara Haya at UC Berkeley, and also William Anderegg based here at the U. And just wondering what response you’ve received on that proposal?

Libby Blanchard

You know, it was published last week and it’s always exciting to get something out into the public sphere. I would say the response has been really positive. There are a lot of groups, particularly in Europe, that are trying to see the contributions approach gain some traction. And so, I’ve got some really nice responses from folks there.

And then I also got a question which comes up a lot with this is how do you incentivize companies to buy into carbon credits or just contribute to projects that might not be quantified through the current carbon crediting framework? How do you incentivize them to continue buying in if they can’t say that they have offset their emissions? And my answers are along the lines of what we’ve talked about. You know, it’s a much safer way for them to talk about what they’re doing when they’re contributing to climate mitigation. And it also frees them up in a very interesting way. So instead of looking at their residual emissions and then trying to match those emissions in a ton per ton framework to achieve net zero, they can look at their residual emissions and say, we have a set amount of money. How do we invest this most effectively? Because in the current carbon market it’s all about getting the highest quantity of carbon credits at the lowest price versus if you’re looking at impact instead of quantity, you can start to have some very interesting conversations about where is our money best spent and could we contribute it to innovative projects that might not have quantified emissions reductions yet, or do have quantified emissions reductions, but outside of the carbon crediting framework, or even buying into really high quality carbon credits. But then again, saying that those credits are helping the company contribute to global climate mitigation, and not to say that those credits are actually offsetting their emissions.

Ross Chambless

Yeah. Well, one other topic I just wanted to mention, so I understand you were also part of a carbon credit working group last year. That was just a group of collaborators working on this issue from other institutions, including a number of folks here at the U. And I’m just curious if you could talk about a little bit about that process and how that group came together and sort of how that has informed the process in your thinking in this area?

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, that group was really fantastic. You know, I’m pretty fresh out of my Ph.D. and so it was the first working group that I got to be involved with. And it was really fun, amongst other reasons, because I felt like everyone in the bibliography of my Ph.D. was sitting in the room with me. And so, it was great to meet all the people whose books I’ve read and whose thoughts have really informed my thinking.

I was trained as a social scientist, and it’s also been really great to be here at the University of Utah because I’m more surrounded by the actual physical and climate scientists who have done the deep work to show the problems with carbon credits to really drill down and show the problems with their additionality, whether they’ve actually caused I see this actually reduced or remove CO2 emissions.

And then with Dr. Anderegg and his work showing the challenges with carbon storage in forests being durable due to risks of insects and disease and wildfire. And there is also a really well-known and respected researcher in the room who’s done a lot of work to look at the albedo effect on tree planting projects. And the idea there is if you plant trees in the wrong place, in a place that if you plant, say, dark trees, in a place that traditionally has really light soils or snow in the wintertime and is reflecting back into the atmosphere, that those trees might be absorbing carbon but might have a net climate…

Ross Chambless

It seems like that study might indicate that in those cases that planting trees in that area might actually be counterproductive to the goals, the overall goals of reducing atmospheric warming, perhaps?

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, it has a warming impact because of the dark colors in an area that is traditionally more light. So, current carbon crediting protocols and methodologies don’t account for that yet. So yeah, it was a great working group and a lot of really forward-thinking people looking at how to do this better, how to quantify these projects more accurately, and how to talk about them more accurately.

Ross Chambless

Fascinating. Just a couple more questions while we have you here. First, what do you envision, what are your goals from here on out as far as the next year or so with your research and what are you hoping to accomplish?

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, I have a few papers. One is in peer review right now and another one I’m working towards submitting in the next couple of weeks. The one in peer review is just a little bit of a deeper dive on the contributions model and how it might work in a policy context. And then the second one is just a project that I’ve been interested in looking at the history of the contributions model and who originally proposed it and why and what can we learn from attempts to incorporate it currently. So I’m going to be kind of wrapping up that contributions work with that paper, though. I’ll still be really excited to talk about it and continue your publishing efforts on it.

And then another project that I’m excited to really get working on is looking at companies with efforts to achieve Net zero. And look at how they’re going about doing that. So, this is back in that offsetting framework. But I’m really curious to delve down into company ESG reports and look at whether they’re actually increasing or decreasing their direct emissions before they buy carbon credits, because it would be really interesting to look at whether carbon credits tend to incentivize or disincentivize companies from directly reducing their emissions.

Ross Chambless

Yeah. That would be that would be quite interesting. Before when I did research for our conversation, I learned there have been a few studies from various groups in the last few years identifying that that is a as a problem as far as some companies might be over relying on carbon offsets as a strategy?

Libby Blanchard

Yeah, that’s the worry. But this is complicated research, and a lot of the data is a little bit hard to come by because a lot of companies aren’t disclosing how they’re getting to their emissions reductions goals. And I’d say the other thing about the current studies is they are looking at correlation between the two variables. And if I can find enough brilliant minds to work with me, it would be really interesting to figure out a way to look at real causation of whether these carbon credits are incentivizing or disincentivizing emissions reductions.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, fascinating. I’d love to hear maybe down the road, if you dive into that topic, what you learn and find out. I think that’ll be a great conversation maybe for another podcast.

Libby Blanchard

Definitely. I’d be happy to be back.

Ross Chambless

I guess the last question I had is on the personal side. What do you do in your free time? What do you do for fun when you’re not hard at work doing research?

Libby Blanchard

You know, I joke that my husband’s first love is skiing, but my first love has become skate skiing in the last few years living in Utah. And climate change really has an effect on it. You know, right now, the place where we usually go to skate ski doesn’t have enough snow this week to go skiing. And so, we’re having to drive further up to Park City to do that.

Ross Chambless

And to clarify, skate skiing is sort of like when you have short skis or what?

Libby Blanchard

Skate skiing is like Nordic skiing, so on the flats and on the rollers, but not riding the chairlift. Yeah, I do think about that’s what I do for fun, but it also makes me think about climate change and what a different world we’re going to be in in another 20 or 30 years. But I would say that I am really excited and motivated with everything that’s happening here at the University of Utah. And the Wilkes Center is just absolutely excellent and is really moving the needle on a lot of really important issues. And I’m very excited to be involved with it.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, absolutely. Well, Libby Blanchard, thank you so much for talking with us.

Libby Blanchard

Thanks for having me.

Related Articles and Links:

https://ssir.org/articles/entry/forest-contributions-carbon-offsets

https://scholars.org/contribution/comments-integrity-council-voluntary-carbon

2 thoughts on “14: Should a “Contribution” Approach Replace the Struggling Carbon Offsets Market?”

Comments are closed.