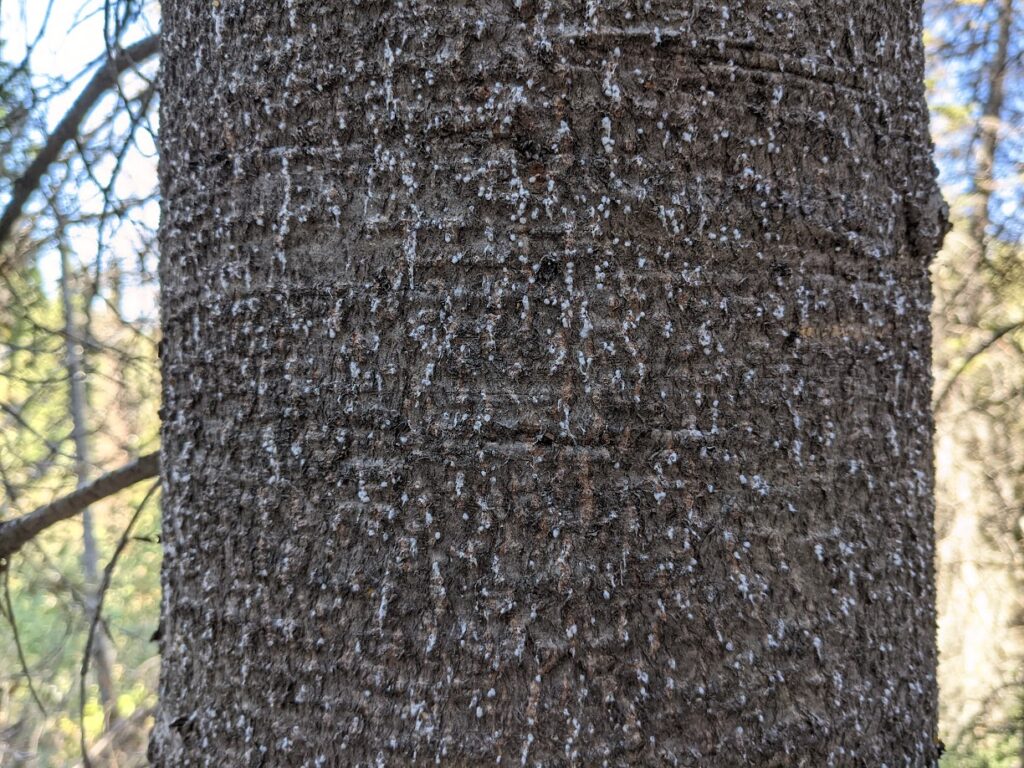

If you’ve taken a hike or a drive through northern Utah’s forests recently, you may have noticed that some areas of the forests are changing and looking a little sick. Northern Utah’s forests are increasingly experiencing an infestation of a tiny non-native insect called balsam woolly adelgid (or BWA), that’s slowly attacking subalpine fir which are among the most common conifers in the Wasatch Mountains. Dr. Mickey Campbell was the lead author of a recently published study that maps the spread of balsam woolly adelgid in Utah. He’s a research assistant professor in the Department of Geography (soon to be renamed the School of Environment, Society, and Sustainability.) I had the chance to talk with him about doing the study and what it means for the future of our forests, as well as his generally philosophy on doing solutions-focused science that can hopefully lead to real-life impacts to policies and practices.

Listen to the Interview:

Transcript:

Ross Chambless

All right. Well, Mickey Campbell, welcome to the work center.

Mickey Campbell

Yeah, thanks for having me.

Ross Chambless

Before we just start off, maybe. Do you mind just sharing a little bit about your background? Just a brief introduction about where you’re working now and what kind of work you’re interested in.

Mickey Campbell

Sure. Well, I consider myself a geospatial and remote sensing data scientist, so really, that means I’m interested in spatial problems of any kind. Sometimes that involves, you know, analyzing aerial imagery or satellite imagery, usually with the goal of addressing some kind of contemporary environmental issue or natural resource management issue. So, I work a lot in the world of forestry and forest ecology and also wildland fire.

Ross Chambless

Okay. Very interesting. Well, let’s start with your most recent research. You recently published a study that looks at a non-native insect species that’s attacking trees, subalpine fir conifer trees here in northern Utah. And your study finds that this is a relatively new insect outbreak to be spreading across forests here from the northwest and west. So, how is this new? What’s happening?

Mickey Campbell

Well, it’s new in the state of Utah, but this is actually you know, it’s an insect that’s been around in the U.S. for over a century. So originally came from Europe. And it is non-native. It’s an invasive insect. There were separate introductions on the East Coast and the West Coast. And so, the population of insects that we’re seeing now in Utah, of course, spread from the Pacific Northwest, kind of east and south. And we’re only first detected in the state of Utah in 2017, though it’s likely that the insect arrived somewhat before that. But yeah, only in the last 5 to 10 years have we started to realize the effects that the balsam woolly adelgid is having on subalpine fir trees in the state of Utah.

Ross Chambless

So now, I understand this is a non-native species. So where did this balsam woolly adelgid originate from?

Mickey Campbell

To my understanding, Central Europe. I don’t know much beyond that. You know, again, it came in the early 20th century, so it’s been here for quite some time. And it’s really been wreaking havoc on true fir trees. So, trees belonging to the genus abies. And in our region, we basically have two abies species, we have subalpine fir, and we have white fur. And BWA, or balsam woolly adelgid, does infest both of those tree species. However, interestingly, the subalpine fir appears to be much more severely affected by BWA. So, for whatever reason, white fur is able to resist BWA’s effects. But Subalpine fir we are seeing some pretty profound effects up to and including tree mortality, in severe cases.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, I see. So, the subalpine fir, I’m sure a lot of people are familiar with them if they venture up into the canyons here locally along the Wasatch Front, right. It’s a very common conifer.

Mickey Campbell

Here it is. It’s among the most common tree species in the state of Utah and certainly in the Wasatch and in the Uinta mountains. If you get up above, let’s say, 7000 feet, that is one of the most common trees you’re going to see in that range. It’s pretty characteristic. If you’re trying to identify it on the landscape, it’s typically the skinniest kind of tall conifer tree. They can be up to a hundred feet tall. But they’re typically very narrow. So, a way to kind of visually identify a fir tree or a subalpine fir tree and distinguish it from a white for weight first tend to be big and broad, you know, large canopies, whereas subalpine fir these are narrow conically shaped trees.

Ross Chambless

I see. So, what do you see as the role of climate change with this outbreak?

Mickey Campbell

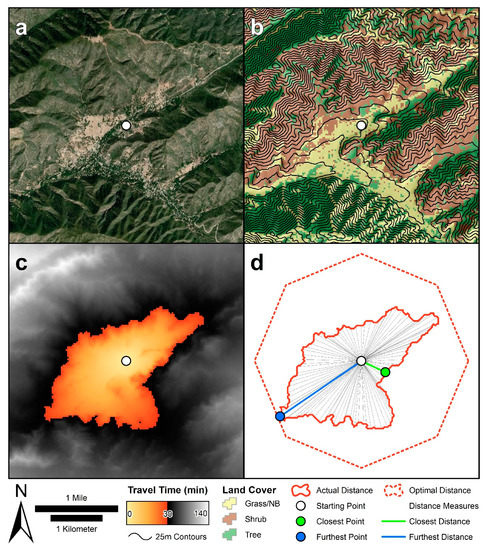

Yeah, so that was one of the major findings of our study. We were trying to identify the characteristics, the landscape characteristics, it could be environmental, topographic climatic characteristics that are linked with high severity infestation. What we wound up doing was testing a whole bunch of different variables. We tested satellite imagery, we tested topographic variables, climate variables, and what we found in comparing measurements we made in the field of how severe the effects of the insect are to these various variables, we were able to distill it down to basically four climate variables that were able to explain most of the variability in severity. And really, they were all related to temperature. So, the prevailing trend is that warmer areas are those that are experiencing the highest levels of BWA severity. So naturally in a warming climate, an insect that has higher severity impacts in warmer areas, the effects are likely to expand both spatially, right? So, warmer areas getting larger, but also the severity increasing in relatively warm areas already.

Ross Chambless

Interesting. So, I guess you developed a model essentially from the results of from your research? And I see it’s an online interactive map of sorts. And I guess the aim is to show future current and future projections of forest impacts across Utah in the West. So, what does this model show and why did you decide to create this visualization tool in the way you did?

Mickey Campbell

Yeah. So, I think with respect to the visualization tool, so many times in the sciences we publish papers and a relatively small number of people read them or, certainly experts in the field have access to them. But it’s relatively rare to be able to share data directly with the public. So, for the sake of this study where, subalpine fir and this phenomenon is so novel in our region, we wanted to be able to provide the general public with access to understand what the future of forests in our region might look like. So yeah, we generated a model that essentially related ground-measured balsam woolly adelgid damage severity to these climate variables. And since they’re all temperature based and we can project what those temperature variables will look like into the future, we were able to map not only kind of current exposure to climatic exposure to BWA, but also what it might look like in 2040, 20, 60, 2080, and 2100. And, by and large, as I said, the trend is in a warming climate. An insect that prefers or causes greater damage in warmer areas is likely to expand and get worse over time.

Ross Chambless

I read that you partnered with the Forest Service for the study, right. So, what is their interest, and how do they sort of plan to use this research?

Mickey Campbell

Yeah. So, I give a lot of credit to Justin Williams, who introduced me to the insect. He worked for the Forest Health Protection Program with the U.S. Forest Service. And he was the one who was already doing a lot of work with balsam woolly adelgid. He approached me in 2020 and basically told me about this insect, told me that it’s a relatively new phenomenon, and mentioned that there hadn’t really been a comprehensive mapping effort. So, when I came into this world, we had a general understanding of where BWR was and was not in the state of Utah, but there was really no spatially explicit map that had a representation of how severe the effects were of the insect everywhere in northern Utah.

So, that was kind of goal number one of the project — let’s map this thing. Let’s get a sense for how severe the effects are and where the effects are most more or less severe. So, the Forest Service certainly has a vested interest in understanding kind of the spatial patterns of where BWA is better or worse just to get a handle on where forest health is likely to be most significantly impacted now. And then the future climate projection piece of the puzzle was getting a sense for potentially proactively where we can understand and ideally mitigate the future effects of where the insect is likely to expand into the future.

So, it’s fundamentally… most of the subalpine fir trees in Utah are on Forest Service land, right. By just the way that Western landownership works out, most of the high elevation forests are managed or owned by the Forest Service. So, knowing how significantly this invasive insect is going to affect this massive resource in subalpine for forests is definitely of high interest to the Forest Service.

Ross Chambless

Right. And we should also mention ski areas, right? So many of the ski areas where people love to ski should be concerned about this as well, right?

Mickey Campbell

Absolutely. I mean, anybody who recreates in the Wasatch or the Uintas and that includes skiing, that includes hiking, climbing, whatever the activity is. Nine times out of ten, if you head up into the Wasatch to do some form of recreation, you’re going to run into a subalpine fir tree. And so you imagine a world in which the balsam woolly adelgid has had the opportunity to spread and caused damage in these forests. And it certainly is going to impact recreational quality. Nobody wants to hike through a forest with a bunch of standing dead trees. So certainly, if nothing else it affects recreational value. But of course, subalpine fir trees and other tree species play many, many critical roles in terms of regulating carbon, cleaning the air, soil retention, snowpack retention. They play so many critical sort of ecosystem service roles. And so, to lose vast quantities of these trees in our region would have pretty devastating effects.

Ross Chambless

Can you remind us about what is the general state of Utah’s forest ecosystems now? Because I think those who pay attention to the health of our forests, they’re probably aware that we have had these sorts of ongoing outbreaks of native bark beetles that have been going on for the last at least a few decades. And that’s been a challenge for Western forests. So, this this seems to be adding on to that. How does that relate to what has been going on with the bark beetles?

Mickey Campbell

Sure. Well, I mean, forests in the western U.S. are faced with a large number of potential threats and agents of change. And as you mentioned, they include bark beetles, but also drought, also fire, there’s pathogens. There’s many, many sources of potential damage that oftentimes work in concert to negatively affect tree health. So, for example, in subalpine fir when we were collecting data in the field, it wasn’t as straightforward as, “Oh, balsam woolly adelgid is killing this tree,” right? We often joke that… Justin Williams, who’s really the entomologist who without whom I couldn’t have done this project. He was kind of a tree mortality detective in a sense. Because you see a tree that’s has declining health or is even dead and you’re basically trying to work backwards and say what caused this? What sort of conditions led to this event? And almost always, it’s not just one thing. Sometimes it’s very clear, like a lightning strike killed this tree. Or, a fire killed this tree. Or, somebody cut this tree down. Like, there are straightforward examples.

But when it comes to things like insects especially, it’s usually a combination of factors that are working together to drive health declines in trees, and that includes bark beetles. So, oftentimes bark beetles and BWA or balsam woolly adelgid will work together to kill a tree. And maybe the balsam woolly adelgid comes in and weakens the tree. And the bark beetle takes advantage of the weakened tree and kills it off. Or maybe it’s vice versa. So, there’s any number of pathways that can lead to tree health decline. But often it’s not just one thing. It’s really the compounding forces of a variety of agents of change that can negatively affect tree health.

Ross Chambless

In your study, I read that you indicated that it generally takes about 3 to 5 years to kill a tree. And that probably factors in all these combination of stressor factors?

Mickey Campbell

Exactly. So, I think that’s an important distinction from other agents of change, too. So, wildfire is very fast, right? It can kill a tree almost instantly. Harvesting timber kills a tree instantly. Bark beetles will kill a tree much faster because they kind of come in, they infest the tree, and they move on to the next one, right? Balsam woolly adelgid is kind of a slow killer. It’s unlike other agents of change in the sense that populations will move into a particular stand, they’ll infest trees, but it’s not like a few weeks or a month, it’s over the course of several years. So, it is kind of a slow decline in tree health that ultimately can and does lead to tree mortality.

And that actually makes it really challenging to map because, again, one of the first things we tried in the study was to look at satellite imagery. Satellite imagery is really good at identifying temporally discrete change events on the landscape. So, if a fire comes through you look at a satellite image from before the fire, you look at a satellite image from after the fire, and I know a fire burned these trees, right. And that can happen in the course of a day, or a week, or a month.

In the case of balsam woolly adelgid, you look at a satellite image, let’s say in 2020, and you look at a satellite image, a year later, and you start to see some declining health, but it’s not instant, right? It’s a long-drawn-out process. So that actually posed a particularly unique challenge to mapping BWA’s effects in our region. And I think that’s why climate data really played such a key role in understanding where balsam woolly adelgid effects are relatively more severe in addition to the satellite data that we were able to combine those two things and really get a good sense of where BWA’s effects are most severe.

Ross Chambless

In and you mentioned that white fir tree species seem to be more immune or were largely resilient, right? Did you have any insight into as to why that might be?

Mickey Campbell

Yeah, that’s a good question. I don’t know that we actually have a perfect understanding why that might be the case. I don’t know this with any degree of certainty, but potentially it has something to do with kind of the distribution of the trees in our region. But you know, that being said, there are examples of known infestation of white fir trees that are just able to withstand the effects. So, potentially it’s just some kind of internal defense mechanism that these trees are able to sort of mitigate BWA’s potential negative effects.

Ross Chambless

Interesting. And so as far as thinking about what might be done to prevent or slow this infestation, do you know if there’s any known remedies? I know with the bark beetle, there are these sorts of pheromone-based applications that you could attach to trees to kind of ward off bark beetles from attacking certain trees. But, have forest managers in other parts of other forests that have already been dealing with this, have they applied any kind of actions to try to prevent it?

Mickey Campbell

Yeah, as I understand there have been some efforts to try to understand potential pesticides that would kill BWA. I think the sort of broad scale of infestation at this point and how diffuse it is — it’s not like you have one little tiny population of BWA that’s hitting this one localized stand — it’s very diffuse. It’s very spread out across the landscape. And it’s millions of acres that are infested. So, if you think about what that would look like in terms of trying to broadcast some application of pesticides, it’s not a tenable solution.

So, I think more of the conversations surrounding how to address the BWA problem are twofold. On one hand, thinking about how we address the effects of subalpine fir trees that are already severely infested. And that could include, if all of these trees are going to die, then we potentially have a bunch of standing dead wood on the landscape, which becomes a fire hazard. So, sort of a retroactive way to address BWA’s effects is to remove deadwood from the landscape so as to avoid other potential issues, including fire.

But, the more proactive approach is considering how to potentially remove trees that are in early stages of infestation. Again, it’s on such a broad scale that even that is really difficult to apply. More realistically, it could just be accepting the notion that subalpine firs are by and large going to be negatively affected on broad spatial scales in our region, so proactively promoting trees that are resistant to BWA. So, identifying trees that cohabitate with subalpine fir and either planting them, or at least supporting their existence in the future so as to avoid a situation in which you go from forest to non-forest, right?

Because that’s a massive ecological shift. If you just change the composition of a forest, you still fundamentally can act as a forest and still provide a lot of those ecosystem services. But if you just let subalpine fir go away, without any sort of proactive management strategies, that can be a pretty important and significant ecological shift.

Ross Chambless

Yeah. Wow. This is going to be a tough challenge and certainly something to keep an eye on going forward in the next few years.

I just wanted to pivot away from this current research project you did and just ask just a few questions about some of the research projects you have done and in past years. I saw on your website that you wrote — and I really like this quote actually — you said, “I am not a “science for the sake of science” type of scholar — I am someone who thrives working on projects that will have meaningful outcomes with clear impacts. You know, that sounds like you’re really hoping that your research makes an impact in the fields of policy and practices in the real world.

Mickey Campbell

Yeah, I mean, I like having some kind of motivation that is grounded in a tangible land management-based solution, right? And that’s not to say anything against people who do science for the sake of science. There is that obviously really important need for basic science. But I think the thing that keeps me going is working on problems that have meaningful solutions and actionable solutions. So not just trying to make up a problem to solve it but understanding that there are real problems out there and trying to leverage my skill set, which is working with big spatial data sets, working with remote sensing data to try to develop solutions that can yield some actual tangible solutions.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, absolutely. I saw that you did some interesting work on wildland fires and specifically models that could assist firefighters who are working on the front lines of fighting fires to avoid dangerous situations. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Mickey Campbell

Sure. That’s a perfect example of trying to engage in science that doesn’t necessarily gain you the most citations, doesn’t necessarily lend itself well to publishing in big journals like Nature and Science, right. It’s seemingly kind of a niche of a field.

During my PhD, along with Phil Dennison, who was my Ph.D. advisor and now very active collaborator, we kind of recognize that firefighter safety is obviously a pressing challenge. Fires are getting bigger. Fires are getting hotter. They’re getting more abundant, more frequent. And still, despite all the advancements in technology, firefighters are still the ones on the ground who are digging lines in the dirt to stop the spread of fires. So, they’re the ones who are really bearing the responsibility for keeping everybody safe and in a world of increasing fire.

But the problems that firefighters face are inherently spatial. They’re what’s the fastest way to get from where I am to some safe location? And what is the quality of that safe location? And how much of my surroundings can I perceive? What are my potential obstacles to situational awareness? All of these things can be mapped, right? And we recognized that early on, and we’ve been working for the past decade to develop solutions that rely on spatial data and modeling to develop, again, actionable, tangible solutions for people who really can use all of the information that they can get to stay safe and do their job more effectively.

So, yeah, we’ve been working really hard on a variety of problems related to firefighter safety. And we’re closely partnering with the Forest Service. And there’s a lot of interest in the work that we’re doing there. And we’re happy to see it starting to turn into not just science that gets published in papers, but science that gets applied on the fire line and directly used by firefighters themselves.

Ross Chambless

Yeah. Well, super interesting. I guess the next question is what do you foresee is next? Do you have any research projects in the pipeline?

Mickey Campbell

Yes! Lots of them. I mean, specifically related to the Balsam woolly adelgid problem, I actually just had a meeting a few minutes ago where we’re talking about expanding this work spatially. So, getting a broader regional sense of how we might be able to map Balsam woolly adelgid’s effects up in Idaho, for example, where BWA has had a longer residency and has really seen much more severe effects because it’s been there longer. But trying to get a handle on where BWA is and isn’t on a broader scale, I think would be really valuable.

Working on a variety of problems related to the firefighter safety still. Trying to, again, turn our solutions into models that are directly applicable and ready to be used by fire management agencies in the U.S.

I’m always interested in tree mortality, so, working on a project related to trying to map tree mortality across the western U.S. So, a variety of things all kind of under the umbrella of forest ecology and wildland fire through a spatial lens, basically.

Ross Chambless

Very cool. Well, excited to see what direction that goes for you. Final question, this is more of a question of what recommendations, or advice, or insight you might have for students who are interested in engaging scientific research and breaking into this field, whether it is forest ecology, or in the fields of geography, such as the directions you’ve taken. The Wilkes Center is, among various things, we really try to empower and nurture future scientists working on climate change issues. So, just curious if you had any advice for those students who would be listening?

Mickey Campbell

Sure. Well, I mean, I think a few things. One, don’t be afraid to sort of try to break new scientific ground in a place that may not seem like it has much fruit, but those areas of research that potentially seem somewhat niche or potentially seem somewhat less productive can sometimes be the most productive, right. Finding those little avenues where it’s like, why has nobody tackled this problem, right.

Again, I’m thinking about the Balsam woolly adelgid, this is a problem that’s been around for a long time. Yet nobody had come up with a way to map it in a robust, reliable way. And so, on one hand you could think about that as, well, if nobody’s done it, there’s probably a reason nobody’s done and I shouldn’t do it. On the other hand, you could say, well, let’s just give it a try, right?

Trying new things and not being afraid to get negative results. Not being afraid to have your weeks or months of effort be sort of not yielding anything super impactful. That’s fine, you know. It’s totally fine to spend a month or two chasing a rabbit down a hole that ultimately doesn’t have a fruitful or productive end, because it’s a learning process.

And I think that’s really where the fun happens, is when you’re trying to chase something and you don’t know if it’s going to work out. And sometimes it does and sometimes it doesn’t. But when it does, the feeling is great personal satisfaction. And of course, a contribution to research and science is always really personally and professionally rewarding too.

Ross Chambless

Awesome. That’s great. Well, Mickey Campbell, thank you so much.

Mickey Campbell

Yeah, thank you. It’s been fun. Appreciate it.

Related Resources and Links

https://mickey-campbell.weebly.com/

https://apps.fs.usda.gov/r6_decaid/views/balsam_woolly_adelgid.html

https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/30d0be9db7c54be19dd11ae22c53122f/

https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/30d0be9db7c54be19dd11ae22c53122f/page/SSP126/