Perovskites are crystal structures that can be manufactured in labs for making solar panels. They are relatively cost-effective, and efficient, and could provide a reliable thin-film alternative to the more common silicon-based solar panels.

However, perovskite solar cells face a few challenges that must be addressed before they can become a competitive commercial PV technology. In some forms they can be unstable, and lead can be a toxic byproduct when processing them. And yet, perovskite-based materials also could have green energy potential beyond solar as batteries and alternatives to modern refrigerants that use chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which are strong greenhouse gases.

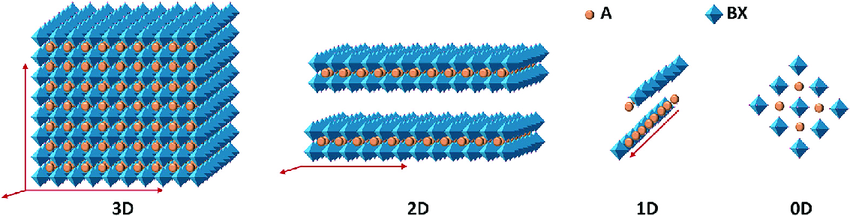

That’s why Jyorthana Muralidhar is fascinated by perovskites. She is a Wilkes Center-funded postdoctoral researcher working in Professor Connor Bischak’s Lab, in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Utah. There she spends her time manipulating 3-dimensional, 2-dimensional, and 1-dimensional perovskite crystals into various combinations and shapes – all with the hope of discovering a new combination that could become the next clean energy breakthrough.

Recently, Jyorthana had some time to talk about her research.

(An image of an ethylene-glycol based 1D perovskite created by Jyorthana Muralidha in her lab by melting and solidifying the perovskite into a ‘U’. Go Utes! (Image courtesy of Jyorthana Muralidhar)

Listen to the Interview:

Transcript:

Ross Chambless

Jyorthana, welcome to the Wilkes Center.

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Thank you. Thank you for inviting me.

Ross Chambless

Just tell us a little bit about your background. What were you doing before you came to the University of Utah?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

So, I basically consider myself as a material chemist. I design and develop materials. I study the chemical and physical properties and useful applications in energy storage and optoelectronics. I particularly focus on perovskite materials. Before I moved to the U, I was in Japan. I did my Ph.D. and a year of post-doc in Japan. So, during my Ph.D., I was working with perovskite materials for ammonia storage. And that’s how I developed interest on the perovskite materials.

I also been reading a lot of articles and papers on global warming challenges. And to be honest, during my Ph.D., the material science field and perovskites, they were new to me. Because my undergrad and grad were basically in biology. So, the material science was a pretty new field to me. I had to literally learn from A to Z. That’s probably how I developed an interest in this particular field. It’s like a blend of my academic experiences and the general knowledge towards the global challenges.

Ross Chambless

I understand currently you are working on two separate research projects. Essentially, you’re working on two different types of perovskites, which I understand are these crystal-like mineral structures. They’re commonly used for processing into solar cells, and they can take on different forms and sizes. They’re one dimensional, two dimensional, three dimensional. Tell our listeners a little bit more about what these are.

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Sure. So, perovskites are any material that has a structure similar to calcium titanium oxide. Calcium titanium oxide was discovered by a German mineralogist whose name is Gustav Rose. He discovered it in the Ural Mountains of Russia, and he named it after a Russian mineralogist, Perovski.

Perovskites have a general formula, it’s ABX3. So, you can imagine calcium, titanium and oxide. The calcium is A, titanium is B, and the oxide is X. So, A and B can be any cations, and X is anion. Usually, it’s halides. Researchers usually play around with the A-site, B- site, and X-site to develop different kind of various structures. But generally, the perovskite has a three-dimensional structure. So, you can imagine a Rubik’s Cube. That’s a general structure three dimensional perovskites. How it forms 3D is based on the metal halide. That’s the B side. Usually, they form octahedron structures. So, if the octahedra are packed like 3D networks, it forms a 3D structure. And the A-site, that’s the cation that I mentioned, in the ABX3 formula, the A is usually packed in the spaces between the octahedra.

When you change the size of the A site, if it’s bigger, it usually disrupts the octahedra. That’s how it forms a lower dimensional structure. So, when you increase the size of the A site, and the metal halides are arranged as into sheets, it is two dimensional structures. If it might form chains or rods. That’s called one dimensional. And they also have a tendency to form zero-dimension. Zero dimension means they have discrete metal halides. They’re not linked as a chain or like a sheet. That’s zero dimensional.

Ross Chambless:

Okay. And so then tell us more about the focus of your research projects specifically.

Jyorthana Muralidhar

So, I’m focusing on low dimensional perovskites. The 3D perovskites have very good properties, especially they have been used in solar cells. For example, the methyl ammonium lead iodide, that’s a three-dimensional perovskite that has been widely studied for the perovskite solar cells. But still, they degrade at ambient conditions. So, the stability is very low when you expose them to moisture, or heat, or sunlight. So that’s where the low dimensional perovskites come to the rescue. So, researchers focus on low dimensional perovskites because they’re highly stable at ambient conditions. So, it can be the two dimensional or the one-dimensional perovskites.

I guess there’s a lot of study on the two-dimensional perovskites because it’s easy to synthesize those perovskites when compared to the one dimensional, because they are forming sheets. I guess it’s easier than forming chains. There have been a lot of reports on the phase transitions of 2D perovskites and blending 2D with 3D for the perovskite solar cells. Probably that’s how I started having an interest in one-dimensional perovskites because it’s less explored. And my Ph.D. project was also on one-dimensional perovskites, So I learned a lot about one-dimensional perovskites. And I also realized that it’s been less used for different applications. So that’s where I wanted to focus on the phase transitions of the one-dimensional perovskites where it can be used for predominantly energy storage or solid-state refrigeration.

Ross Chambless

So, perovskites, how common are they in the world? Where are they typically found or mined?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Mining, it’s probably the calcium titanium oxide is what they mine. The origin is Russia. As I mentioned earlier, the Ural Mountains. Apart from Russia, they are also mined in Italy, Switzerland. I think they do it in the U.S. also, if I’m not wrong, it’s in Arkansas?

Ross Chambless

I see. So, they can be quite commonly found in various places around the globe.

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Yeah. Calcium titanium oxide can be found in various places. But in terms of research, we design and synthesize perovskites. So basically, as I said, we play around with the A-site. A can be the alkyl ammonium chains. B can be any metal like lead, manganese. And X-site can be halides, like iodine, chlorine, or bromide. So, basically it just has to be a structure similar to the calcium titanium oxide. So, in terms of perovskite research, I think it’s just different structures and different atoms.

Ross Chambless

I see. There’s great interest in this right now across the world because we’re in this energy transition, and there’s a lot of interest in finding new ways, new processes of developing renewable energies such as solar cells or batteries. And looking at these one-dimensional, two-dimensional perovskites could have a lot of promise if we can figure out, like exactly what you’re working on, how to do it in a way that’s efficient and environmentally safe. Let’s talk about that, because I understand that the typical process for currently processing perovskites, especially the three-dimensional ones, can include some hazards. Can we talk about that?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Yeah. So, the typical perovskite contains lead. I think that’s the major issue with the perovskites. Lead is highly toxic to the environment. I think it’s not the essential metal such as a manganese, or zinc, or copper. So that’s where the researchers are trying to replace lead with manganese, or copper, or zinc so that it’s less hazardous. I guess there would be some changes in the properties because you’re changing the metal. But still, in terms of working towards the green application, I think the manganese and copper and zinc, they do a pretty good job compared to lead. So that’s how we are working on the led-free perovskites.

I’m also doing a project where we’ll be able to melt these perovskites. So basically, when you make a film using a perovskite, you have to dissolve the perovskites in high boiling-point solvents. So, you dissolve it and you make a solution. Then you either spin coat or drop cast, and then you have to heat it up to evaporate the solvent. And that’s how you make films. So, the meltable perovskites, they don’t need any solvent. You can just melt them between 100 to 150 degrees Celsius. You can melt them into liquid, and make a film, and then just dry them. You can just cool them to room temperature and make a film out of it. So, in that way you can eliminate the need of solvents because the solvents are also hazardous to the environment.

Ross Chambless

Right. And potentially what you’re saying is that being able to melt these at a much lower temperature could have a lot of benefits?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Yeah. So that’s also a part where the researchers are focusing on, the suppressing of melting temperature. Because the general solvents that we use, the common ones that we use for making perovskite solutions are DMF and DMSO. They usually have a boiling point around 150 to 180 degrees Celsius. What we are trying to do is to tune the perovskites. As I said, you can play around with the A-site, and B-site, and X-site, so you can change the length of the A-site of the cations. In that way you can suppress the melting temperature. So, I’ve been working with the ethylene glycol-based perovskites. They usually melt around 120 degrees Celsius. I’ve been trying to blend them with different lengths of ethylene glycol chains. And we were successfully able to suppress the melting temperature to 98 degrees. So, that’s pretty low when compared to…

Ross Chambless

Even below the temperature of boiling water?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Yeah.

Ross Chambless

Wow. So, you’re essentially investigating sort of these phase transitions with perovskites and testing the process for which these materials potentially could be changed or processed into a condition which would be good for moving and converting into solar cells or batteries in a more efficient way.

So, when we’re looking at these materials physically in front of you, do you need a microscope, or can you just see them right there in front of you? How large are there? What do they look like?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Actually, they’re more like poly crystals. I guess the 3D ones, they have pretty big crystals. But in case of two-dimensional and one-dimensional, they are more polycrystalline like very small crystals. But if you could see on the microscope, you can see a very clear crystal. But we usually do the X-ray analysis to study the structure. But from the naked eye, you can just see the powder or the poly crystals.

Ross Chambless

Okay. And I wanted to pivot a little bit back because you mentioned that these materials can be used as refrigerants, as alternative to refrigerants that we commonly use — the hydrofluorocarbons — which we know can have very high global greenhouse gas emission potential. Could you talk a little bit about how your research impacts that?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

So researchers have been studying a solid-to-solid phase transition in perovskites, especially to replace traditional refrigeration where it uses some hydrofluorocarbons. As we know, the refrigerants that’s actually liquid, made of hydrofluorocarbons, they are really toxic to the environment. So how the refrigerants work is they also undergo phase transition. And that phase transition is liquid to gas.

So, you know when the appliances get old over time, there can be a leakage problem. That’s how the hydrofluorocarbons escape into the air. So, to overcome this issue, researchers are focusing on solid-solid phase transition materials. Looking into solid-solid, there’s not going to be any liquid, there’s not going to be any leakage. And obviously there’s a phase transition taking place, but it’s not going to emit any harmful gases.

The solid-solid phase transition depends on what kind of perovskite material you have synthesized. For a good material to act as a solid-state refrigeration, it should have high entropy. Entropy is the degree of randomness. So, you know with solid, liquid, and gas, the gas has a higher degree of randomness. They just move around freely, right? So that’s how the solid-solid phase transition means. They should have a high entropy, high degree of randomness. And they should have low hysteresis. Low hysteresis means, take an example of ice melting. Ice melts to a liquid, water. So, water has a melting temperature, and water has a freezing temperature. If the difference between the melting and the freezing temperature is what is called hysteresis. So same in case of the solid-solid phase transition. So, the temperature of melting and temperature to recrystallize, it should not be large.

Basically, a large entropy and very small hysteresis, is what makes a material good for solid-state refrigeration. So, researchers are playing around with the crystal structure and chain-tuning the crystal properties, tuning the cations and anions of the perovskites, inducing defects, doping. They’re trying to make a good material for the solid state refrigeration. And that’s what we are also working on.

Ross Chambless

I see. Really interesting. So, the thinking is that potentially if you figure out the right mechanism, these materials could be used as a product that could be used in refrigerators or, everything we need refrigerators for, right. Heating or cooling, essentially in our daily lives, and not have to rely on these toxic materials, hydrofluorocarbons. How do you feel that research is progressing?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Oh, it’s pretty good. I think it’s very interesting because we are developing novel perovskite structures. introducing new cations, anions blending. So, playing around with the structure is really interesting, and we never know where we end up. We try making two-dimensional perovskites, but we end up with one-dimensional perovskites. We think this perovskite is going to have this kind of property, but interestingly, it might show up with a different property. And that’s how we build novel perovskites with novel properties. So, it’s been interesting. And my work has so far been good. I’ve finished a project. I’m almost done with the meltable perovskites. I’m focusing on the solid-solid phase transition as I mentioned before for the solid-state refrigeration. So, I’m working on one-dimensional perovskites like the methylammonium lead iodide, trying to replace ethyl with trifluoro. And I’m planning to tune the halides and metals and see how the properties are, and whether they would fit for the heating and cooling system.

Ross Chambless

I see. I understand part of your project ultimately is to develop a prototype device in some way?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Hopefully.

Ross Chambless

Do you think that’s not far away?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Yeah, as I said, it just takes time to find the right material. Even though we know the mechanism, I think still, researchers are struggling on finding the exact mechanism to get a good material for the solid-state refrigeration. We’re still trying to find the best one. We are tuning the structure and seeing if it would work.

Ross Chambless

Who else is working on this that you’re aware of as far as your work on one-dimensional perovskites? Anywhere. Across the country or across the world?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

I don’t think any group specifically works on one-dimensional perovskites, because as I said, it’s kind of difficult to control the dimension between 1D and 2D. Even though you know the size of the A cation, if you know the length of the chain, sometimes the chain is going to form loops. So, you never know what exactly the size of the A-site is, because the A-site is going to determine the dimension of the perovskite. So you cannot control the dimension, especially the one at or 2D. So, I don’t think any group focuses particularly on 1D. There are groups that work both on 1D and two-dimensional perovskites such as our group. But the work that I’ve been doing now, there are few groups, especially from Professor David Mitzi. He works on the phase transitions of 2D perovskites and multiple perovskites. So, I’ve been reading a lot of papers from him. Another one is a Professor Jarad Mason. He studies solid state refrigeration and 2D perovskites. So, both groups have been a big inspiration and really helpful for my current research.

Ross Chambless

Very interesting. Some of the work you were doing previously with your as a doctoral researcher in Japan also dealt with chemical storage, you mentioned ammonia, but also working with perovskites. How did that work inform, or inspire, or lead you to doing to be interested in the work that you’re doing now?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

During my Ph.D., I was working on ethylammonium lead iodide. That’s a one-dimensional perovskite. Basically, perovskites they tend to have the ammonia sensing nature. There have been reports where perovskites are studied as ammonia sensors. So that’s how we started the work. We wanted to make a good ammonia sensor using one-dimensional perovskite. And then it turned out like a storage medium. So, we studied how it undergoes a chemical reaction when it is exposed to ammonia gas or aqueous ammonium. And it can eventually store ammonia.

So, ammonia is like a carbon free hydrogen storage medium. We thought why not use this perovskite as an ammonia storage medium instead of a sensor, because with sensors there are reports there are also other very effective sensors compared to the one-dimensional. Like if you take the three-dimensional perovskite methylammonium lead iodide, which is black in color, when you expose it to ammonia, it turns yellow. It’s a very effective ammonia sensor. But the ethylammonium lead iodide I was using, it’s yellow, and when you expose it to ammonia, it turns white. You can actually use it for an ammonia sensor. But I think storing ammonia is more effective than an ammonia sensor because that is what the world really needs. We are working towards the global challenges, right? We need a carbon free…

Ross Chambless

Yeah. decarbonized.

Jyorthana Muralidhar

… hydrogen storage medium. So that’s how we used the 1D perovskite as ammonia storage medium. And since I’ve been reading a lot of literature related to ammonia storage or carbon-free development of perovskites. I eventually developed interest on working on 1D-perovskites and for other kinds of applications. And the current group, the Bischak group, they work on phase transitions and solid-state refrigeration. So that’s how I thought, why not use 1D perovskites for solid state refrigeration.

Ross Chambless

Well, I wanted to ask sort of pulling back and looking at the bigger picture, what keeps you motivated with your with your research? How much do you think about the long-term implications or potential for the work that you’re doing now to change the world, to improve the world?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Um, I’m not sure if science really works that way. You usually think of making a material for a particular application, but you end up with something else. And I think most research works that way. You just accidentally end up with something great, right? So, I believe in developing novel materials, which has novel characters like novel properties, and surprisingly they would fit in different applications that we never realized. So, I’m actually focused on designing and developing materials and then gradually focus on the application.

Ross Chambless

Okay. Well, what do you enjoy most about your work now?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

I’d say learning new things. Because as I mentioned, I’ve been trying to design and develop novel materials. I think that’s a part of an interesting research. And thanks to my PI, he gives me the space to work and explore different materials. I think learning new things especially, you will see failure in research. So, it doesn’t matter. You learn new things from failures too. That’s what makes the research very interesting.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, I guess. Are you enjoying your time here at the University of Utah? I mean, are you do you feel like it’s meeting your expectations or your career goals?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Yeah, I’m having a great time here. I think that’s one reason why I moved to the U. Because, as I mentioned, I had a great interest in working with perovskites in different applications. Because usually if you say perovskite, it’s just the solar cells, right? So, they never use it for different applications like the solid-state refrigeration or energy storage, thermal energy storage. I think that part of the research is very less (common) compared to the solar cells. So, I wanted to focus on different kind of applications for the perovskites. As I mentioned before, Bischak group has been working actively on developing new perovskite materials, their phase transition, looking into their energy storage applications, or the heating and cooling systems. So that’s the reason why I moved to the U. So, I think it’s definitely a good opportunity for me because I’m able to do what I’m interested in. I’m having great time here at the U.

Ross Chambless

Well the last question really is what do you do for fun? What do you do when you’re not focused on your research?

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Uh, I’m more of a homebody. I enjoy being at home, like cooking and just relaxing when I’m not working or doing the research. I used to travel a lot, like explore new places, explore new cuisines. But I don’t know if I’m just aging, but I just like staying at home and relaxing. spending time with my husband.

Ross Chambless

Yeah, understood. Well, Jyorthana, thank you so much for spending time to talk with us and share your research.

Jyorthana Muralidhar

Yeah, Thank you. I had a great time talking to you.